I’m very honored to participate in the auction organized by the prestigious art foundation in New York

“THE GLASS HOUSE”

I’m very honored to participate in the auction organized by the prestigious art foundation in New York

“THE GLASS HOUSE”

Territories of Complexities

WhiteBox

March 29th – April 5th

Curated by Lara Pan

By Mark Bloch

http://artistorganizedart.org/commons/2017/04/bloch-paturel-whitebox.html

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

“Territories of Complexities” was an appropriate name for this exhibition at WhiteBox. There was much more going on than met my eye that was not apparent from the start.

The nine large, seemingly squarish, seemingly abstract paintings unidentified by individual names that were exhibited on the walls of this large, squarish, indeed, white box-like space seemed earnest and straightforward. The show was a competent “suite” of works by a middle aged artist making fine art for just seven years after a couple of decades in the field of architecture.

But the more I looked, the more the works expanded within my field of vision. Then a chat with Guillaume Paturel, born in Marseille, France in 1970 and a graduate of L’École des Beaux Arts in Marseille with degrees in art and architecture enhanced my perception further. Finally, a tenth piece, a game changer, was added to the show between my initial visit and the opening, casting in concrete, well actually in plywood, the connection between art and architecture, the artist and his subject matter: surface and depth. It raised the stakes for me as a viewer as it raised the artist’s stratum in which to work from the second dimension into the third.

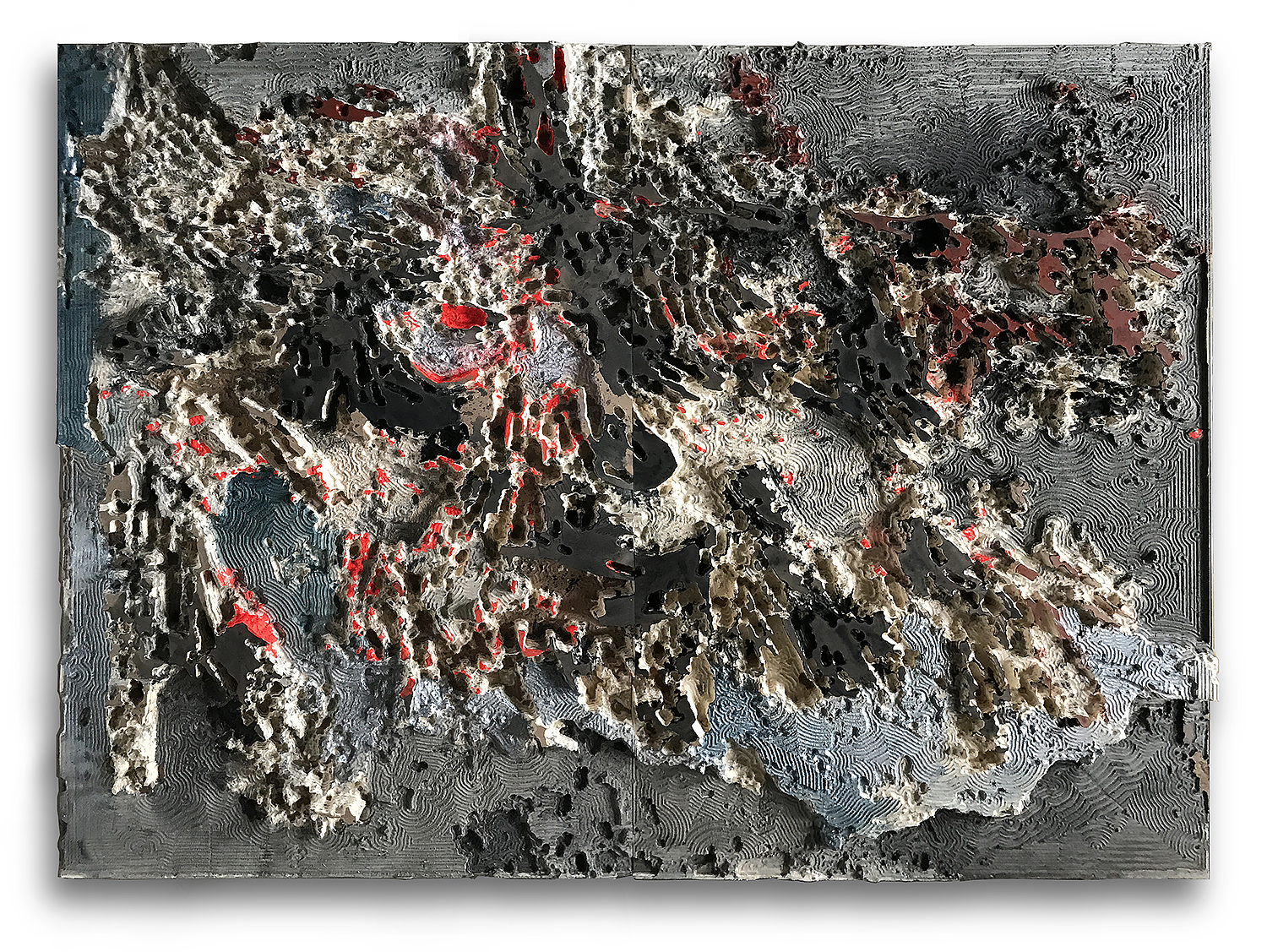

Though the artist Paturel and the curator Lara Pan, both alerted me that the new piece would be installed before the opening, I was not prepared for what I saw when I reentered the gallery. A striking “sculptural painting,” that Pan called “his first foray into the medium” now expertly occupied the center of the space, displayed close to, but not directly on, the floor, horizontally. This 4” thick solid wood slab had been ground, gouged and burrowed out by a robotic arm to create a topographical 3D object, fabricated directly from a painting now hanging behind it, behind the hand-painted peaks that seemed to be ascending ever so gently toward the ceiling like a hybrid between an accordion and an alien planetary landscape, and like the collaboration between man and machine that it really was. The texture was all machine-made. The inspiration and added color were by the artist.

That painting the sculpture “borrowed” from, and the other eight adjacent to it, were not square I now learned, merely by taking a second look and using my left brain, something not particularly engaged during my first visit. I could see that though similar to each other, these nine paintings, five or six feet across in either direction, were each unique in size, orientation and in the amount of power with which they projected energy into the space, toward the 3-D addition in the center of the room that, as a projection of one of the mostly “flat” works that surrounded it, seemed to bring them all into sharper focus.

Like the work seemingly hovering above the floor, each work on the walls contained silver, echoing the artist’s still thick head of hair, catching bits of light but not reflective. The nine pieces gently fought each other like extra terrestrial weather maps indicating chaotic, violent patterns traveling over coarse, scaly, abrasive, bumpy, scratchy planes aggressively, each supported by its own thick wooden structure and charting its own course. One was all silver. One was black with only silver wisps. Others were speckled and punctuated silver or shiny white or off white with a silvery sheen—with dotted tape textures and other colors emerging from below. Some had their supports painted dull black, others had other colors splattered on them and still others boasted only their raw wood grain as a foundation.

My first impression had not been correct when I first entered the space because their surfaces, seen from afar, appeared regular and monochromatic, polished, possibly smooth, ironed, slippery and fine—like so much of what one sees in galleries these days. But instead, these were what Paturel later described as his ideal: “dusty, ugly stuff.” They were, in fact, bumpy, sandpapery, scabby and cracked. When I asked the French man what he thought of American Ab Ex, he informed me that, to him, his art is not at all abstract. He sees his works as depictions of landscapes, geography, scenery, ground, and landforms. Any abstraction I detected was just the result of layers that courageously cover mysterious terrain underneath, which in turn cover thick skins of maps or guides, both of which alternatively familiar and confounding to the artist, I was assured.

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

Paturel still produces architectural renderings for some of the world’s top architects. Following the Beaux Arts, Paturel also attended Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris La Villette.

These paintings were, therefore, similar to topographical meanderings, but simultaneously important escape hatches from his work as an architect, needed imaginary extensions of the professional work he does for important sites like the new One World Trade Center tower and memorial or a sustainable city in Saudi Arabia. He is a gifted craftsman in both jobs, apparently. He recalls that before he was “tied to a computer” he had created, in a previous version of his profession, architectural renderings using handmade collage techniques with whatever materials were necessary to eek out his visions of practical structures not yet realized.

So perhaps missing that mode of handmade expression, he explains that these less practical works begin with the laying down of aluminum tape, building layouts of non-existant “cities.” His memory wanders through memories of previous projects for sites in The Bronx or Red Hook (where he now lives with his family) or in Dubai, where clients “asked for trees and grass and beautiful greenery” in the architectural renderings, but adds that once finished and he was on site, he witnessed “just landscapes of dirt and sand and policemen.”

And so he applies layers of paint. He scrapes to unearth underlying strata. On their exterior, these artworks show evidence of nicks and cuts and gouges, the surface forcefully indented creating external damage indented and intended and invented.

He told me that he does not favor the slick, cute, happy superficiality he sees in the work of many artist contemporaries. He prefers art like opera, showing passions or deep truths that elude us so I ask for his personal story, hitherto unavailable in my investigations. He looks at me long and hard and finally asks, “Do you really want to know?” I do. He tells me his work is not abstract, so I wonder, what is it? “My art fights death,” he tells me. “Creativity against decay, you know?” He finally volunteers that he is now an artist because he once told a lie then had to fight for his life to make it true.

His father called him to reveal he was fighting cancer one day out of the blue seven years ago in New York where he had moved after decades of them not speaking. From there they carefully rekindled their rocky relationship. Guillaume told him he was about to have a show, but it was a lie; there was no show. He was an architect, never an artist. But after he hung up the phone he went directly to the store and bought art supplies. He next arranged to have an exhibition and set to work.

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

As Guillaume watched his French father’s health drift in and out from afar, for the next seven months, he became an artist. He fought by creating his topographical worlds with memories of the bourgeois accents of his native Marseilles echoing in his head.

Guillaume reluctantly told me that at age seven physical abuse by his father was rationalized by telling him it was because of the “improper ” way he spoke for a boy from Marseilles. He thus descended from speech to stuttering and then to silence, as the whole topic of language became an enemy. Then at age 11 or 12, as suddenly as his speech had been beaten out of him, he fought his way back from 5 years of complete silence with sheer willpower, and learned to talk again, just as he became a self-taught fine artist only seven years ago.

Determined as he is, he does not like the headstrong way the builders of New York City clear empty lots for their architectural sites for new buildings. When they cart away the rubble, sweep away the refuse, remove the layers of detritus and dust and the urban patina, it breaks his heart. So perhaps he uses paintings to savor the currents of necessarily unpleasant emotion, unleashing and then covering them up again.

Under the tortured surface of silvers and blues punctuated by tiny reds, yellows or light greens, flows of metallic tape and pigment emerge like flows of electricity in his work, like the movement of electrically charged particles traveling in feathery shapes or colliding like shiny geysers or in matte areas hiding in shiny black.

Where my perception was once of cleverly concealed dispassionate, phlegmatic gestures, now that I’ve heard his story, there are patterns suggestive of vulnerably turbulent water or air in motion. Not smooth or polished surfaces but pockmarked, irregular geomorphology. Uneven, chapped, rugged and wrinkled membranes of trapped language.

I ask him again what artists he likes. He finally mentions Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer. While Kiefer’s works are characterized by an unrepentant willingness to face his culture’s dark past, Guillaume confronts his own past, more similar to the media-shy Richter, an artist who does not want to talk about his work. Paturel’s art is speech that says something that part of him does not seem to want explained.

“My pieces are cities, territories, urban landscapes either deserted or under construction,” he says. “My city of choice is geometry and chaos, order and disorder, verticality and stratification.”

So let us return to the 3 dimensional horizontal piece in the middle of the room. He fabricated it with the help of some architectural colleagues from one of the paintings in the show that they turned into a digital photo and then into software that extrapolates information into 3D to create “tool paths” which tell a machine how to carve in 3 directions, at 5 different pivot points, ultimately directing a “CNC router” to carve away designated areas of the 4” thick slab of wood that stretches out as wide as the paintings on the wall do—again, 5 or 6 feet rectangles. Form burrowed away in concentric irregular rings around elevated surfaces look like tiny islands in vast oceans. To these surfaces and large areas of wood where the color in the original painting was converted to raised land masses, the artist added new layers of color, different from its topographical doppelganger, hanging on the wall behind it.

While the technology and the technicians did a spectacular job of recreating in three dimensions, the original turbulent layers of paint and texture, subtle and not-so-subtle, complete with tape interruptions and handmade scrapes and scratches, the painting that it was derived from takes its orders from a kind of plan that robotic arms and digital code can imitate and simulate and even expand in untold new dimensions, but never understand. Despite continued clean, tidy attempts to the contrary by the contemporaries of Guillaume Paturel, art is capable of unearthing suppressed language that whispers, sometimes desperately, sometimes mysteriously, but if we listen, complex territory is revealed.

Guillaume Paturel was born in Marseille, France in 1970. he earned degrees in art and architecture from L’école des Beaux Arts in Marseille and Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris la Villette. He has produced architectural renderings for some of the world’s top architects, including Sou Fujimoto, Didier Faustino, Mos Architects, Maurizio Pezo, and Sofia von Ellrichshausen. Other highlights include renderings for the new One World Trade Center Tower and Memorial and K.A.Care’s sustainable city in Saudi Arabia. Paturel is also an accomplished filmmaker whose works have been shown in film festivals in france and switzerland. Paturel has had solo exhibitions of his paintings in New York City at Fragmental Museum (2012), One Art Space (2013), and A+E Gallery (2015).https://guillaume-paturel.squarespace.com/

Mark Bloch (American, born 1956, www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Bloch) is recognized as being one of a handful of early converts from mail art to online communities.In 1989, Bloch began his experimental foray into the digital space when he founded Panscan, part of the Echo NYC text-based teleconferencing system, the first online art discussion group in New York City. Panscan lasted from 1990 to 1995. Following the death of Ray Johnson in 1995, Bloch left Echo and began a twenty-year research project on Communication art and Johnson, and wrote several texts on him that were among the earliest to appear online and elsewhere. Bloch and writer/editor Elizabeth Zuba brought together an exploration of Ray Johnson’s innovative interpretations of ‘the book’” at the Printed Matter New York Art Book Fair in 2014 at MoMA PS1. Bloch has since acted as a resourcefor a new generation of Johnson and Fluxus followers on fact-finding missions.

WhiteBox, located in NYC, is a non-profit art space that serves as a platform for contemporary artists to develop and showcase new site-specific work, and is a laboratory for unique commissions, exhibitions, special events, salon series, and arts education programs. WhiteBox was founded in 1998. http://whiteboxnyc.org/

DATE:March 29th - April 5th

“MY PIECES ARE CITIES, TERRITORIES, URBAN LANDSCAPES EITHER DESERTED OR UNDER CONSTRUCTION. BEING FRENCH, LIVING IN NEW YORK, MY CITY OF CHOICE IS WHAT FEEDS MY INSPIRATION: GEOMETRY AND CHAOS, ORDER AND DISORDER, VERTICALITY AND STRATIFICATION.”

– GUILLAUME PATUREL

WHITEBOX IS PLEASED TO PRESENT NEW WORKS BY THE FRENCH ARTIST GUILLAUME PATUREL, THE EXHIBITION, TITLED “TERRITORIES OF COMPLEXITY” WILL FEATURE A SUITE OF LARGE-SCALE PAINTINGS AND ONE SCULPTURAL PAINTING —HIS FIRST FORAY INTO THE MEDIUM.

PATUREL’S ARTISTIC PRACTICE INTERWEAVES ARCHITECTURE AND PAINTING—THEY NEST TOGETHER, OVERLAP, COMPRESS EACH OTHER, AND COLLIDE LIKE A GEOGRAPHICAL STUDY APPLIED TO THE MEMORY OF MANKIND. HE TAKES AN ALMOST PRIMITIVE APPROACH TO THE MATERIALS, CHOOSING WOODEN PANELS WHICH HE SPONTANEOUSLY CUTS, SCRAPES, AND CARVES THROUGHOUT THE PAINTING PROCESS TO REVEAL LAYERS EMBEDDED IN THE MATERIALS. AT THE MOMENT OF CREATION, THE ARTIST ALREADY HAS A VISION OF HOW TO METHODICALLY DECONSTRUCT AND RECONSTRUCT IN A SUCCESSION OF SUBTRACTION AND LAYERING, TRANSFORMING HIS PAINTINGS INTO AN ALMOST SCULPTURAL ORGANIZED CHAOS.

IN THIS EXHIBITION, PATUREL’S PAINTINGS EVOKE INTENTIONAL ATTEMPTS TO MARK AND DELIMIT A TERRITORY EXCAVATED FROM DENSELY LAYERED PAINT AND PATTERNS AND THE MATERIALITY OF THE WOODEN PANELS THEY OCCUPY. ARCHITECTURAL COMPONENTS ARE OMNIPRESENT IN THE WORK, THOUGH IT IS REVEALED IN A SUBTLE ENERGY AND BARELY DEFINED FORMS, ECHOES OF SCHEMATICS AND TOPOGRAPHICAL MAPS. PATUREL’S PAINTING IS ABOVE ALL PHYSICAL AND MATERIAL. HE TRANSFORMS WOODEN PANELS FROM PASSIVE SURFACES TO ACTIVE SCULPTURAL PAINTINGS. FOR PATUREL, THIS APPROACH OF INSERTING “FOREIGN” MATERIALS INTO PAINTING IS REMINISCENT OF HOW, THROUGH ARTIFICIAL OR NATURAL INTERVENTIONS, ONE CAN TRANSFORM COMPLETELY URBAN AND NATURAL LANDSCAPES.

GUILLAUME PATUREL WAS BORN IN MARSEILLE, FRANCE IN 1970. HE EARNED DEGREES IN ART AND ARCHITECTURE FROM L’ÉCOLE DES BEAUX ARTS IN MARSEILLE AND ECOLE NATIONALE SUPÉRIEURE D’ARCHITECTURE DE PARIS LA VILLETTE. HE HAS PRODUCED ARCHITECTURAL RENDERINGS FOR SOME OF THE WORLD’S TOP ARCHITECTS, INCLUDING SOU FUJIMOTO, DIDIER FAUSTINO, MOS ARCHITECTS, MAURIZIO PEZO, AND SOFIA VON ELLRICHSHAUSEN. OTHER HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE RENDERINGS FOR THE NEW ONE WORLD TRADE CENTER TOWER AND MEMORIAL AND K.A.CARE’S SUSTAINABLE CITY IN SAUDI ARABIA. PATUREL IS ALSO AN ACCOMPLISHED FILMMAKER WHOSE WORKS HAVE BEEN SHOWN IN FILM FESTIVALS IN FRANCE AND SWITZERLAND. PATUREL HAS HAD SOLO EXHIBITIONS OF HIS PAINTINGS AT THE FRAGMENTAL MUSEUM (2012), ONE ART SPACE (2013), AND A+E GALLERY (2015), ALL IN NEW YORK CITY, NY.

LARA PAN

By Goënièvre Anaïs

http://quietlunch.com/new-orphism-guillaume-paturel/

URBAN UTOPIAS ON CANVAS WOOD.

When light takes root in Gowanus

Then, drift off unknown oceans …

Guillaume Paturel’s adventure in painting begins in the heart of Brooklyn’s historic industrial district, Gowanus, a few years ago. Along the canal, iron skeletons lie in the water, calderian accumulations of waste punctuate the landscape, constantly modifying it. The study of plans for his work as an architect and the daily observation of the ballet of the cranes mark him deeply and orient his artistic approach. Today, these visual memories are linked to the Atlantic mist and the constant variations of the sky over Manhattan.

He exhibited at the Fragmental Museum, in Queens (curator: Guy Reziciner), at the One Art Space in Manhattan and at the gallery A + E (curator Frederique Dessemond – Ginette NY, jewellery designer) in Manhattan. He is preparing a new solo-show for the month of March in Lower East Side.

PARIS WITH CIRCLES. | ACRYLIC ON WOOD. | 47.64″ X 71.65″, 2016.

From unknown silence, the matter wells up, unfolds and then becomes organized. The thunder’s vibrant embossment. We distinguish between the clouds, the silver foam from the terrestrial horizons: the feast of the world. With Guillaume Paturel, the eyes swallow “the solemn geographies of human limits” – Paul Eluard. In the well of the canvas, Paturel digs the abstract memory of history’s colors : the flowers’ gist that reborn a thousand times and the evanescent stars’ energy … Underground, sub-canvas, marvel at the red rising from an unsuspected river. Outbreak of the pictorial event. The artist carves, in the leaves of a black gold, the flickering temple of our migrating cities : Black Series 01, Paris with Circles…He transfigures the architectural data into a pleiad of matrix cells: fishes shoals secretly gathered, original symphony’s nucleuses, scattered and choreographed flakes slipping on the dress of the continents.

SOLAR. | ACRYLIC COLLAGE & CARVING ON WOOD. | 69.29″ X 74.80″, 2015.

With Solar, Paturel stares the jolts of a renewed Orphism. Let us remember the words of Frantisek Kupka: “My painting, abstract? Why ? Painting is concrete: color, shapes, dynamics. What counts is the invention. One must invent and then build.” At the beginning of the 20th century, the french poet Apollinaire extends a wire between Robert & Sonia Delaunay’s solar cubism and Orpheus, his poem with the “luminous language”. In the rayonist cave of matter’s decomposition into energetic bundles, artists weave their understanding of the world. Painting, since then, cuts out, with the magnifying glass, the quintessence of the movement. Today, many painters continue this research, in view of socio-cultural, political and geographical strong problematics. At the Whitney Museum of American Art, Mark Bradford’s collages bear witness to this: Bread and Circuses executed in 2007. Bradford and Paturel share this fascination with cities, their carvings, and archeology.

Interpret with the heart’s hands, the sun we populate. Force will be to inhabit the light in communion with the wave announcing creative gesture.

“I have not the feeling that my paintings are cheerful, I even find them quite dark and tragic! For me, they contain an energy: the fight of colors. It is primarily the idea of a battle, of contradictory movements confronting one another. Just as the borders of countries that are under pressure. These are the pressures I am trying to show. The elements, inside a painting, must remain mobile, in circulation …

My paintings always have several readings and even vary according to the hours of the day… So, it’s difficult to choose titles. If this morning “blue” is the answer for one, few days later, an other word comes. Soulages has found an escape: no title. I think about it…”–Guillaume Paturel

By the third oedipal eye, the artist reproduces the anamorphoses of his augmented vision. And the painted picture erects a repair. Dislocated lotus’s scales for a single ship. Enchanted phalanstary with flowing wings. Underwater Zeppelin. Emergency utopias for the bruised peoples. When the oceans rise and collapse on neighboring empires, the artist mends the urban fabric. He reestablishes the vestiges and, under the sand, unveils, by timeless fragments, the possible existences. How to renovate paradise since its deafening?

58. | ACRYLIC & CARVING ON WOOD. | 69.29 X 74.80″, 2016.

The artist works towards that and gives birth to landscapes with multiple fantasy whorls. Its dynamic fables scatter fluid vortices, impetuous reefs, organic cavities.

“We must redeem the world through beauty: beauty of gesture, of innocence, of sacrifice, of the ideal.”

– François Cheng

Was not this also the source of Alberto Burri’s project in Gibbelina, in Sicily? While the city is engulfed by an earthquake the artist explores, in the pictorial thickness, the cracking of the earth in monochromes – with strong touches – until intervening on the ruins of the city, in covering with a white cement the walls of the original streets. Land art or land of reverence … Sometimes, when architecture enters into communion with painting, the piece of art, suddenly, restores the visible’s field.

There is in the paintings of Guillaume Paturel, a remarkable synthesis of a thousand identifiable writings. Inheritances. He borrows from the ancient Chinese techniques, the science of the Breath which caresses, with a stroke of claw, the porous soils of the canvas. Its variations of gray invoke the density of Anselm Kieffer’s works, strata bending under the weight of the past. Regarding modern and contemporary art, the philosopher Lyotard noted: “The works of painting, sculpture, architecture and literature are worth nothing as answers to nihilism, they are all worth as questions posed to nothingness.” Often the lower part of Paturel’s paintings gives way to strokes full of water, a heavy rain which flows in straight lines as if to reveal the plot of the projected actions. We can think of Bomb Island, Black Curtain or Cobourg 3 +1 more, paintings by Peter Doig, dating back to the 1990s.

Painting, as music, has this ineffable virtue: to wander in immensity, to infinity. Does not the substance of expression belong to the power of creating a place? And from its observation shore, the spectator activates the vibration. In 2012, in an interview, Richard Serra confides: “All I can say is that there is a lot of unbearable lightness and entertainment in art. It is a lightness which does not root you, and which is content to clean everything in its passage.” A work is an adventure, a breathing, an innate experience.

detail "catch the beast " acrylic on wood 2.40 X 3 meters -2016

detail "catch the beast " acrylic on wood 2.40 X 3 meters -2016

A+E STUDIOS

160 WEST BROADWAY NEW YORK

OCTOBER 23 2015

view back / credit photo laure chaminas

entrance / credit photo laure chaminas

inside the shelter / credit photo laure chaminas

Current: Gowanus is an art exhibit and sale presented by Arts Gowanus May 14-18, 2014. Curated by Benjamin Sutton, this exhibit will showcase the breadth and depth of visual art that is being made in Gowanus right now. Come on out, take your time with the art, experience Gowanus, and support Arts Gowanus. We look forward to seeing you there!

ARTISTS: Remy Amezuca, Rachel Bernstein, Matt Callinan, Ai Campbell, Kat Chamberlin, Caroline Chandler, Miska Draskoczy, James Ewart, Elizabeth Fiedorek, Veronique Gambier, Tony Geiger, Abby Goldstein, Meena Hasan, Megan Hays, Erik Hougen, Terrance Hughes, Sarah Jones, Sara Jones, Elizabeth Jordan, Suzy Kopf, Hiro Kurata, Jessica Levine, Romina Meric, Rene Murray, Liz Naiden, Phuong Nguyen, Alex Nunez, Sui Park, Helena Parriott, Guillaume Paturel, Sarah Nicole Phillips, Robert Saywitz, Rachel Schmidhofer, Joelle Shallon, Katie Shima, Evan Simon, Shura Skaya, Andrew Smenos, Maya Suess, Denise Treizman, TJ Volonis, Kit Warren, Andrea Wenglowskyj, Justin Whitkin

The mechanical glow and savage potion, the sublime sink and the fluorescent drip. A mix between Rothko and Pollock, Guillaume’s paintings are haunting. They are as profound as the oceans and nighttime skies of which they are echoes, and yet youthful, childish, playful. For me, they contain a certain duality, of open-minded modesty and religious spiritualism, which draws me to them like a bat to a cave. Certainly, they can be overwhelming. But they are not vulgar, and they do not seek to jam some message down your throat. No, they expect more - they set the stage for the viewer to engage with them, to play with them, in the same way you might feel stargazing at night, when the cosmos beckon you to wonder. Their capacity for this interactiveness lies in the fact that they meet that balance between ‘message’ and ‘nothing’ which is precisely where I have often best placed Rothko. Indeed, they carry Rothko’s sacredness, and could easily be imagined in his Texas chapel alongside his other work. And yet they are not dead, they are alive, electric, moving; and it is in that I see Pollock.

BLUE MOON acrylic on wood 1.21 X 1.82 meters -2013

When I asked some close relatives of Guillaume about the meaning of his paintings, they had little to say other than ‘they look pretty’. And in some sense that’s okay: the paintings are not propaganda, they are deep expressions of very human experiences. They might have no ‘message’, but they do have feeling, life, a story. They were painted by someone who had suffered, who had loved, who had won, lost, been frustrated, been angry, been saddened and overjoyed. Someone who’d lived. And that we see also in the art of Pollock and Rothko, whose action paintings and multiforms have a psychological and intellectual depth that could have only been achievable given such ‘life’. Indeed, it is so easy to get caught up in how beautiful their art is so as to forget the price these artists, in particular, paid. What is this price? One of suffering. I believe that it was the same drive that pushed these men to produce such awesome art that did to self-destruction, alcoholism and suicide, as if they had poured all that was beautiful and alive in them into the canvases they are remembered for.

To pause at mere aesthetics when confronted with such disturbingly profound work is lazy, ignorant and inappropriate. Such a point can be expanded to much art today; one would hope that the general public would cease in its obsession with technical ability (‘my toddler could have done that...’) and look beyond to see the sentiments, thoughts and feeling that lay behind. Technical ability is of only relative importance to the quality of an art piece (relative, that is, to the success of expression). To illustrate my point, many machines today posses much technical ‘artistic’ ability than we - photocopiers can copy better, laser cutters can cut more accurately, some machines even paint finer. And yet there is something about a Schwitters collage (whose exhibition I saw at the Tate Britain), with its imprecise cuts and rough imperfections, that will always win over a perfectly laser cut automatic collage-making machine. Why? Because Kurt Schwitters was someone who lived and loved and lost, and we are drawn to that which most resembles ourselves. Because life is not perfect, is not precise, so what is the relevance of art, if art really is to hold a mirror up to nature, that pretends it were? In that sense, then, we are all imperfectionists.

But the idea of meaning crops up again and again. What meaning? What’s the message? Guillaume’s paintings are both post-modern and primitive, and in that sense are utterly human, honest to their maker’s origins. They carry both the caveman’s yearning for sense, and the 21st century philosopher’s grapple with epistemology. They are primitive, raw and unedited in form, and yet done with modern techniques and materials. This in itself is an ironic reminder of man’s endless and unresolved search for meaning in the debris; this is of little coincidence, as Guillaume himself was influenced, visually, by the post-apocalyptic scenes of the Japanese Tsunami, and the immediate struggle for life following it.

In similar vein to that tragedy is the colour scheme of the painting Blue Moon I, which is the archetypal painting: tentative and yet overwhelming. Why tentative? Because somewhere, not completely hidden, in the overarching darkness, there are glimmers of hope, of white, and pink, and red. Why overwhelming? Because the painting gives you very little, the responsibility is overbearing. The viewer is invited on stage by the painting’s subtle ambiguities, and, in this case, he is free to see the glitter of colour as either the beginning or end of hope, he is free to see whatever he wants, and in that sense becomes an artist along with the painter. It is for this reason that Guillaume, when asked what his paintings ‘mean’, has very little to say: as he said to me, ‘J’ai tout a faire et rien a dire’ (‘I have everything to do and nothing to say’).

Undoubtedly, however, there are moments where Guillaume is trying to express a certain idea, thought or feeling. And yet even in these cases, he does not need to answer the question ‘what are you trying to say?’, for the artist need not deliberately think about such things even if he is ‘trying to say’ something. A writer, for example, will live many years before he writes a book. He might regret his childhood, become married, conscripted to war, win against all odds and in the final count lose against mere improbability… so that by the time he writes his book there are many layers of subconscious memory, which will have been rehearsed, reflected upon, edited, processed over time. So it will often be the case that an author will think for a long time. And then he will stop thinking and start writing. And though little of what he writes will be ‘deliberate’, it will all be him, it will all reveal facets or possibilities of the artist’s being. This is because over time the artist will have been shaped and formed by his experiences to become the tool that expresses itself, reproduces. It is for this reason that Guillaume does not like to have his own paintings in his house: he says that one of him is overbearing enough, he needs not see himself everywhere he goes. So what? So art is inseparable from the artist, because it is the artist. Parts of him anyway.

Guillaume’s art? He layers and layers, and in that sense mimics the subconscious. And then he tears layers away, revealing what is beneath. The best way to describe it would be psychological excavation, and in that sense his questions are: what am I really, underneath it all? What is there, once you’ve stripped all the crap away? His art is therefore practical psychology, therapy even.

His choice of wood renders the entire painting an object, a sculpture, which he can work with, expose, boast and manipulate. In his opinion, canvas artists spend too much time concealing the surface, making us forget it. This, in a sense, makes their art less relevant, for it is detached, it is not part of the world. Rather, Guillaume prefers to use industrial and everyday materials, available at any hardware store. His art is therefore in some paradoxical sense ordinary, relevant and relatable. Because Guillaume scratches and sands away surfaces, the viewer can see the many different layers that lie beneath the ‘finished product’. In that sense, too, Guillaume celebrates not just painting but painting: his works boast the process that is the construction of a painting in their display of the work in progress. This, in turn, feeds into Guillaume’s obsession with authenticity, honesty and integrity.

And so? And so Guillaume’s paintings are honest, if anything at all. Like them or not, they’re the real thing. And we can relate to them. Because of their abstract nature (and Guillaume is in the end a self-professed abstract expressionist) the paintings are flexible and change in meaning as the viewer changes. They are playful, demanding. Their flexibility and emotional profundity are marks of the kind of art that is appreciated for hundreds of years, whose constant relevance to the everchanging and yet utterly static human condition will ensure that they do not become obsolete artefacts of a past time, to be stored in a museum, but works that can be engaged with in art galleries by people that will undoubtedly lead quite different lives that we do at the moment.

Importantly, and this is very important, I would like to finish by saying that I maintain that Guillaume’s art is optimistic. It is optimistic in the way that Beckett might be said to be optimistic, perhaps not because of what is being said (though that is up for debate) but simply because something is being said at all. It is a testimony to the ups and downs of life, in all its shit and glory, the loud exclamation that separates us from the silent animals of the slaughterhouse.

@alexandep

NYC25:TOP 25 EXHIBITION DATES

October 25-November 14

568 Broadway, Suite 501

(between Prince St & Houston St)

New York, NY 10012

www.westwoodgallery.com

Facebook / Twitter

From June 13 to June 26 at One art space Gallery at 23 Warren Street, 10007, New York, New York

With Under Construction, Paturel’s focus is on our mental images of cities in natural context. His paintings are like instant snapshots of urban environments and artifacts at critical moments of their development such as their birth, disappearance and metamorphosis. Those critical state let them reveal their logic, inherent utopias but also their materiality, fragility and hesitations.

/ credit photo benoit paillet

From left to right: Photo by: Benoît Pailley Project in Antarctic II, 2013, Acrylic and Collage on Wood, 47″ x 95″; Project in Antarctic I, 2013, Acrylic and Collage on Wood, 47″ x 95″; Highway & Clouds, 2012, Acrylic and Collage on Wood, 71″ x 71″

In the wide and desert Antarctic series of paintings, while mixing cool and warm colors, natural elements reveal their strength besides the movement that Paturel creates with the layering of coats of tape collage. Guillaume Paturel relates this series to birth. The paint is scratched, sanded to reveal the stratification of elements, since our planet is a layering of mineral elements of plate tectonics, being constantly displaced. Creation in a natural environment is one of the main focuses in the exhibition Under Construction.

The hurricane Sandy that hit NYC and completely destroyed Breezy Point in Queens inspired the painting Highway and Clouds, as the cloud came and took away every trace of life, leaving the landscape free to a new birth.

First solo show at the fragmental museum curated by guy reziciner, long island city new york may 2012.

19 pieces are shown into 10 000 sq ft.

/ photo credit benoit paillet

/ photo credit benoit paillet

/ photo credit benoit paillet